To return to Master page click on ‘Flowers’ above.

SLHS: Flowers Brewery Life

Disclaimer

Whilst some care has been taken to check externally linked websites no responsibility is offered nor implied for the suitability, legality or reliability of content therein.

Statements are made here to the best of our knowledge. However no statement here should be regarded as irrefutable fact. Please contact us if you consider otherwise.

Brewing Skill

Brewing is not a process that can just be stopped and started at will because many of the processes, for instance, require heating for a time and moving on to the next stage at just the right time. Not only could the brew fail but alterations in timing would affect quality. Consistent good quality is what kept drinkers coming back for more. Therefore all of processes from gathering the ingredients through to pouring from the beer pump required skill and attention to detail. Yeast is a relatively fragile live organism and thus even careless cleaning of vessels or utensils could harm the flavour or make useless a complete brew. Thus reliability of suppliers and staff were paramount.

Good Staff Were Key

In the light of this brewers not only had to retain good key staff they had to retain knowledgeable ordinary staff otherwise simple mistakes could mean entire batches would be unfit and the good name of the brewery marred.

Benefits In Kind

Of course manual labour in the countryside meant that workers would migrate seasonally. Even in the towns in the 19th century workers were quite adept at moving from job to job based upon how much pay they could earn. Morale was important. Timely production methods required staff to be careful and motivated so it’s not surprising that brewers provided bonuses as encouragements.

Further Information..

-

Simple guide:

-

Excellent detailed article:

-

● Full

-

● Partial

-

● None

-

Theatres ●

Last update: 30/11/2024

Created: 18/11/2024

“Christmas Beef”

Jonathan Reinarz[1] explains..

-

“In the early 1880s, employees regularly began to receive what was known as 'Christmas beef. During the holiday season, Flower & Sons' workers each received a pound of beef married workers received an additional pound and another half pound for each child. In 1882, one of the first years for which such records exist, the brewery distributed more than 460 pounds of beef to 176 workers. Naturally, at the largest firms, such as Bass & Co, total gifts distributed on such occasions frequently astounded members of the trade, let alone the general public. In 1895, for example, the meat distributed among their hands 'amounted to over 26,000 Christmas beef was also presented to publicans associated with the brewery. In 1882, owners and tenants of sixty houses received winter bonuses. Not all publicans, however, received 'Christmas beef. Depending on the amount of ale sold, publicans received as much as thirty pounds of prime beef, or, alternatively, should business have been sluggish, a single hare. Variations in gifts therefore also reveal complicated sales' histories. For example, not all publicans who sold 150 barrels of Flowers ale in a year, a figure which usually denoted healthy sales, received twenty to thirty pounds of beef at Christmas. Should a decline in sales have been apparent, publicans not only received less beef, but often a less tender cut. In 1881, after her sales had declined from 142 to 134 barrels in a single year, Mrs Hawkes, a publican in Bearley, complained to the brewery, as her beef was inferior to that sent previously; not surprisingly, Hawkes did not receive compensation.

-

Alternatively, even those publicans who did not sell as much as others often received an equal bonus if sales had noticeably increased over the year. Mrs Page of Stratford's Garrick Inn, normally allocated a goose at Christmas, was delivered a turkey by one of the brewery's stable boys after sales had improved by three barrels in 1882.

-

Like the ale allowance, the presentation of Christmas meat continued beyond the First World War. Some evidence, however, suggests the brewery had in fact become less generous than in previous years. For example, by 1906, although 200 brewery workers received such a bonus, they took home just under 250 pounds of beef77T he fact that 137 men were married and 108 had children suggests that bonuses no longer went to families, but only to workers. On the other hand, more labourers, namely part-timers, who were not granted bonuses in the past, had been added to the brewery's Christmas list. Moreover, in the first years of the twentieth century, Flower & Sons' holiday bonuses extended to a much wider network, including railway workers, with whom the brewery did a considerable business. Employees of the Great Western Rail Company in Stratford, as well as Evesham, Fladbury, Pershore, Campden, Blockley, Moreton, Shipston and Broadway, received a substantial amount of Flowers India Pale Ale in half-pint bottles. W. H. Doonan, a local postal clerk, also took dozens of pints home during holidays in these years, as did the recipient of perhaps the most questionable of bonuses Mr M. Walters, an officer with the Inland Revenue ! By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the acceptance of such gifts was at least questioned by some authorities.

-

Besides presenting employees with beef in winter, Flower & Sons periodically fed workers in the warmer months of the year, as these years witnessed the firm's first company-sponsored outings. More than simple bonuses, picnics and excursions were to foster good feelings between employees and their superiors, as well as help promote the formation of a company identity. The first of these events appears to have been held in August 1869 when 300 people enjoyed 'dancing and rustic sports' on a field alongside the Avon belonging to Mrs Chambers of NElcote. Participating equally in all amusements, employees' wives and children were served only tea and cake, while men were offered the sustenance of meat and ale. " Perhaps not the first picnic organised by the brewery, it was the first event staged outside the brewery's own buildings, attracted the interest of many of the region's inhabitants and was reported in the local newspapers.

-

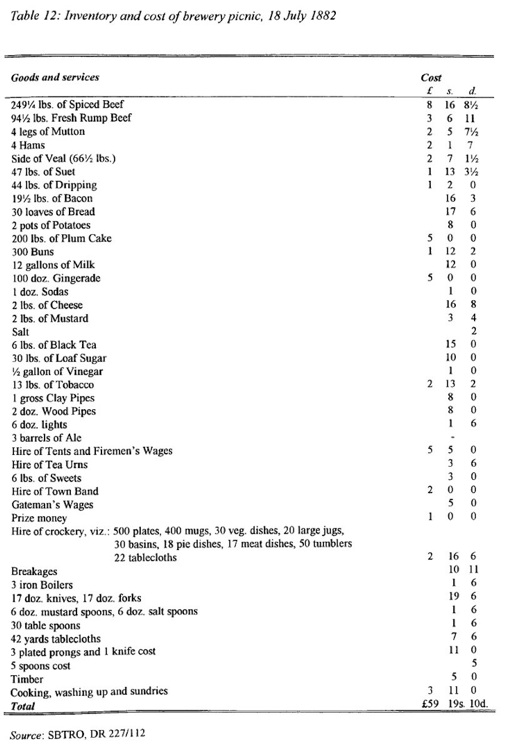

Successive outings were even more elaborate events and were held each year until 1914 when interrupted by war. Approximately a decade after the brewery's first picnic, more than 500 people attended what had essentially become a town feast and required weeks to prepare (see Table 12).

-

The event at which Charles Flower announced his retirement in 1888 resembled a small fair and attracted approximately 1000 guests, including 250 brewery labourers. Having again convened in a local field, guests feasted on several hundred pounds of beef, mutton, veal and pork, along with generous portions of vegetables, bread, butter and various condiments. For dessert employees consumed approximately two hundred pounds of plum cake and smoked a dozen pounds of tobacco; those without pipes obtained clay pipes which breweries distributed on these occasions and in their public houses. Lunch was held in four tents, each of which exceeded one hundred feet in length and had been constructed by local timber merchants, Cox & Son. Employees sat alongside publicans and distinguished guests in four rows of tables which ran the length of each tent and, while most naturally came to enjoy the brewery's ales, milk and gingerade were also in abundance. Besides racing for prizes and competing in a tug-of-war during the afternoon, employees and their families were treated to a performance of the local militia's sixteen-man band. Furthermore, the event provided an income to the wives of several employees who took many days to roast meat, prepare food items, iron table cloths and, eventually, wash up. The picnic also proved profitable for Flower & Sons' enterprising cooper, William Lambert, whose china shop supplied all of the dishes and cutlery used by the brewery's guests. Besides paying for the rental of Lambert's wares, the firm paid for all breakages and, more interestingly, for the disappearance of a large number of eating utensils. The entire affair cost the brewery more than £80; future outings would prove more elaborate.

-

The annual picnic was intended as a treat for workers, who enjoyed few regularly scheduled holidays during the nineteenth century. Prior to the first brewery outing, most labourers' years were punctuated by only the Mop, a local hiring fair, or unscheduled periods of unemployment. 86 In general, brewery workers enjoyed few holidays, most employers having preferred to brew on holidays to keep men in work. "One of the few firms to introduce a week-long, paid holiday in these years was Truman., Hanbury, Buxton & Co." In this sense, annual outings, such as picnics, were an important development, especially for those labourers who worked six or even seven days a week, as was common at the brewery during these years. Clerks and travelers, on the other hand, took regular holidays throughout the 1870s. In fact, as early as 1869, Flowers' travelers were each allotted a ten-day, paid holiday. Most clerks took holidays in late summer when business in general slowed. Few brewery labourers could afford to take any time off work. In 1879, wage ledgers record only two workers who regularly enjoyed a week-long holiday and, as labourers went unpaid during such breaks, usually only coopers or foremen could afford such a luxury. With the development of rail transport, however, greater opportunities existed for workers to take holidays, especially as the brewery, an important customer of the Great Western Rail Company, arranged for cheaper fares or, alternatively, obtained bulk discounts by chartering entire trains. The first such company- sponsored rail excursion took place on 17 July 1885. Presumably the trip was a success, for another was organised the following year. While the earliest rail journeys only took employees to nearbý local sites, such as Aston grounds in Birmingham, later destinations included Liverpool, London and Portsmouth (see Table 13). Other firms organised their own excursions. In July 1896 alone, the editors of the Brewers'Journal reported forty brewery outings. 91 By 1900, even the twenty employees of the Stratford-upon-Avon Sanitary Steam Laundry enjoyed a regular day trip to either Warwick or Leamington.

-

Meanwhile, employees of firms based elsewhere regularly came to Stratford on their own excursions. By 1895, these well-publicised outings, like the brewery's annual picnic, had become regular occurrences. Unlike picnics and other company-centred outings, however, the average rail excursion did not always foster a corporate identity among brewery employees. While labourers occasionally fraternised with non-brewery workers during other social occasions, they were overwhelmed by them during rail excursions. For example, in 1907, when 161 brewery workers travelled to Llandudno, 235 members of the general public, who paid the brewery 5s. 6d. for a day ticket and 13s. for a three-day ticket, also went to the Welsh resort town. Nevertheless, workers were reminded that these trips were organised for their benefit. Besides their free rail tickets, brewery workers received 5s. spending money, while office workers were granted 7s. 6d.”

This was not unique to Flowers. Many brewers had to retain staff similar incentivisations.

-

References

-

[1] Warwick University PhD Thesis 1998 download (25Mb): The Social History of a Midland Business: Flower & Sons Brewery, Stratford-upon-Avon, 1870-1914 pp376

The remarkable extravagance of worker’s outings by modern standards

Annual Outings

Certainly Flowers were not easily outdone when it came to having a ‘jolly’.